What is Metacognitive Therapy (MCT)

Download our best tips on reducing anxiety and worrying

Learn three powerful metacognitive therapy steps to stop the worry cycle, reduce anxiety, and feel calmer in everyday life.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

Metacognitive Therapy (MCT) is an evidence-based method of psychotherapy based on over 30 years of research on the causes of mental disorders and how the mind works. It's making major waves in the field of psychotherapy, as MCT represents a paradigm shift in how mental health disorders are understood and treated.

Metacognitive Therapy is an evidence-based method of psychotherapy based on over 30 years of research on the causes of mental disorders and how the mind works. It's making major waves in the field of psychotherapy, as MCT represents a paradigm shift in how mental health disorders are understood and treated.

The latest research shows that MCT is an effective therapy against a range of common mental disorders, and it’s particularly beneficial for those struggling with persistent worry, rumination, and anxiety.

MCT in a nutshell

'Everyone has negative thoughts, and everyone believes their negative thoughts sometimes. But not everyone develops sustained anxiety, depression, or emotional suffering. An important question is: What is it that controls thoughts and determines whether one can dismiss them or whether one sinks into prolonged and deeper distress?' (Wells, 2009)

This central question was proposed by Dr. Adrian Wells, founder of Metacognitive Therapy. In his search for answers, Dr. Wells made a series of breakthrough discoveries that challenge much of what we thought we knew about the human mind.

MCT provides a new understanding of what causes and sustains mental suffering, enabling a radically different and highly effective form of psychotherapy. As Dr. Wells explains:

'Thoughts don't matter but your response to them does.'

The reality is, we can't control which thoughts pop into our head. But we can decide what to do with the thoughts once they arrive. Metacognitive Therapy is a journey to rediscovering your natural ability to respond to your thoughts without prolonging distress.

Your response to your thoughts is an essential factor in the development of mental health problems. Let's explore how MCT enables rapid recovery from common psychological disorders, such as anxiety, depression, PTSD, OCD, and more.

You can't extinguish a fire with gasoline

We all know that negative thoughts and emotions can be unpleasant. But they're a natural part of life for everyone, and for the most part, they're transient and short-lived. We all experience negative thoughts, and research shows that people with mental health issues don't necessarily experience more negative thoughts than others.

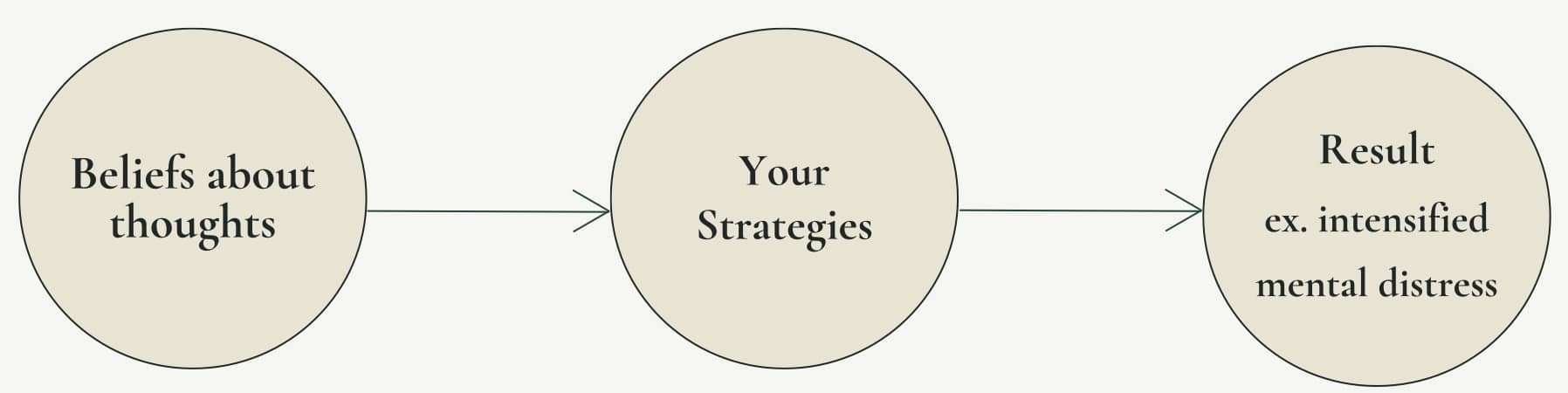

So why do negative thoughts escalate into mental distress for some people? The answer lies in your beliefs about your thoughts, feelings, and symptoms, and your strategies for dealing with them.

It turns out, some ways of responding to negative thoughts and feelings are helpful, and allow them to pass fairly quickly, while other ways prolong and escalate negative thoughts and feelings, leading to mental distress. The very strategies many people use to cope and feel better can actually be the cause of this distress.

It's a concept that sounds counter-intuitive: How can the solution that you believed would help you actually be the problem? The research now shows that if you currently suffer from mental health issues, chances are this is exactly what's happening. It's like trying to extinguish an open fire with gasoline.

Download our best tips on reducing anxiety and worrying

Learn three powerful metacognitive therapy steps to stop the worry cycle, reduce anxiety, and feel calmer in everyday life.

What do you believe about your thoughts and feelings?

Do you believe that worrying is helpful? Can negative thoughts and feelings harm you? Do they need to be dealt with? Is worrying and rumination outside of your control?

We all have ideas about our thoughts, their importance, and how they should be dealt with. And it turns out, these beliefs may hold the key to whether you'll go on to develop a mental disorder.

Research on Metacognitive Therapy suggests that your beliefs about your thoughts are a prime indicator for developing and sustaining common mental disorders.

Your beliefs dictate your strategies

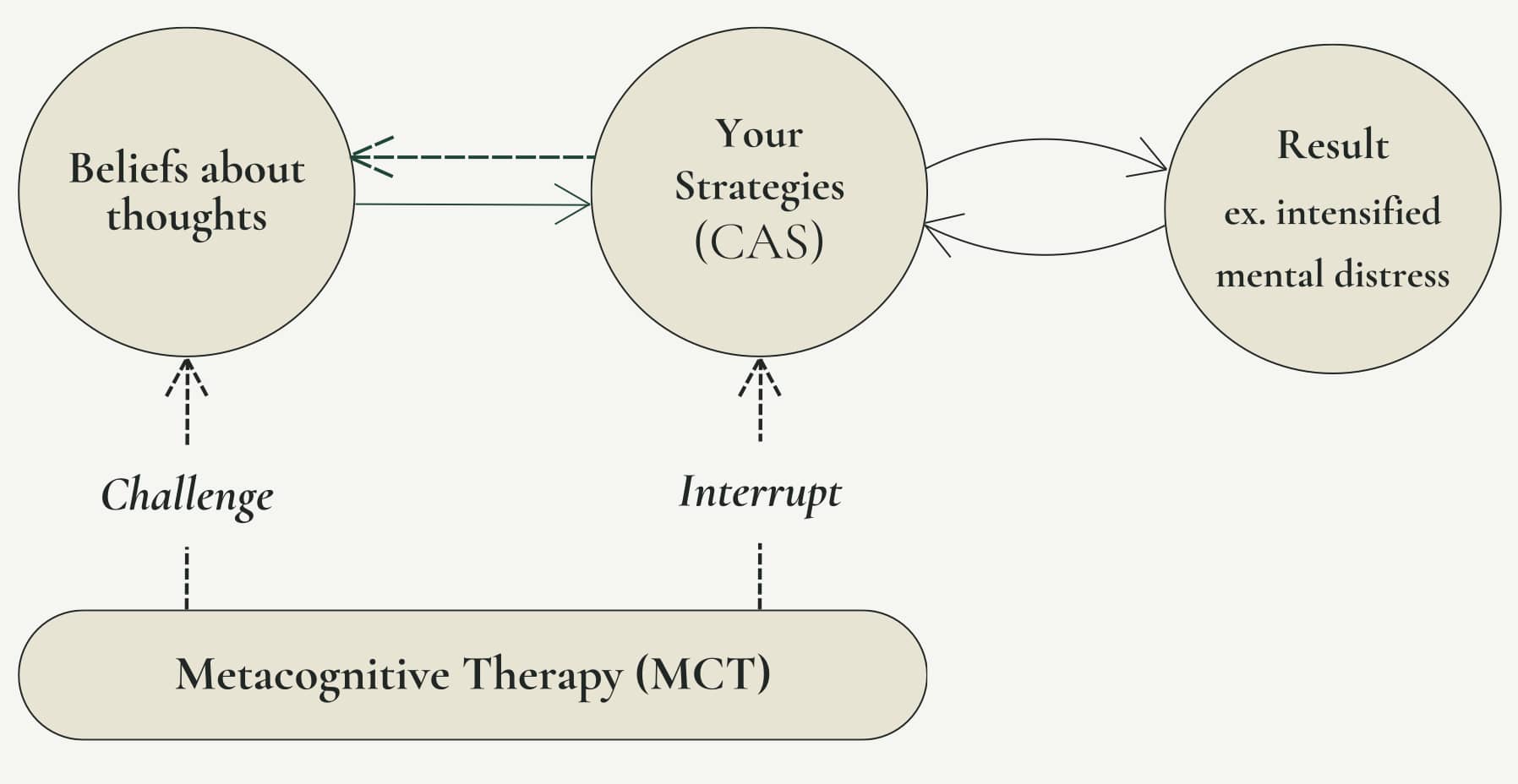

The beliefs you hold about your thoughts are called metacognitive beliefs, and they ultimately dictate your strategy for handling thoughts. Your strategies are your personal weapons-of-choice for dealing with intrusive thoughts, feelings, symptoms, and emotions.

Why are these beliefs so important? Think about what happens when you believe that worrying will help you solve problems and stay prepared, and that worrying is outside of your control. Or when you believe that you need to ruminate on your anxiety to find answers, and that you can't stop this process. Or when you believe that you need to constantly monitor your symptoms to avoid getting a panic attack, but also that you can't stop the monitoring. You're now stuck in a loop of negative thinking, which escalates the original negative thoughts and feelings.

Some people believe the exact opposite: That it's not necessary to respond to every thought that pops up. Or that intrusive thoughts will pass on their own if you just let them be. These people typically avoid getting stuck in cycles of rumination and overthinking.

This is where we start to see a very clear division between people with and without mental health struggles.

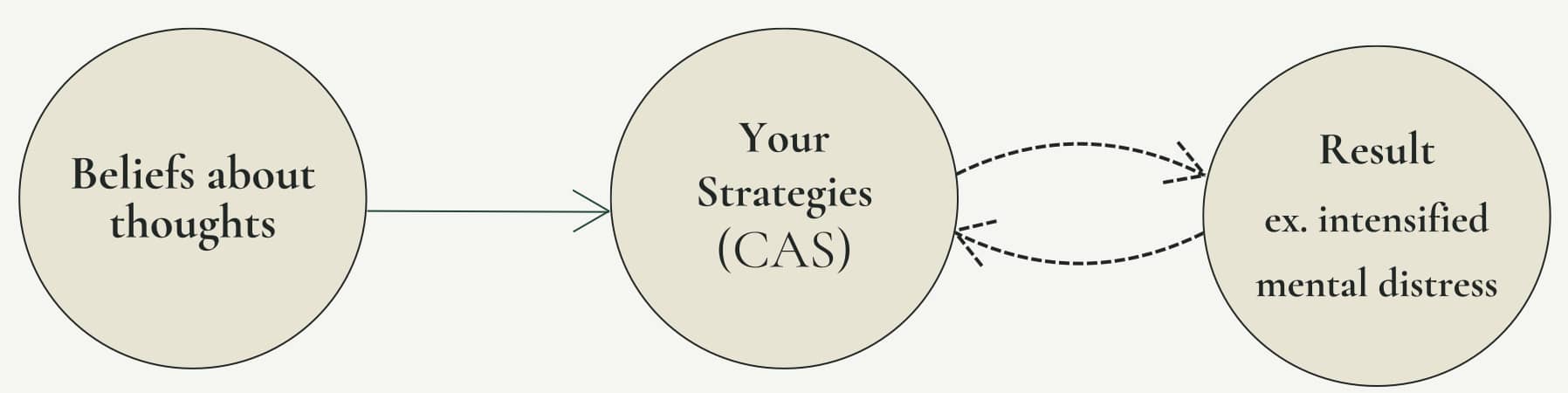

CAS: When the medicine becomes the disease

We now know that the strategies people often use to deal with emotional distress may be causing or amplifying it.

Let’s examine some common beliefs and how they could affect your strategies and mental wellbeing.

If, for example, you believe that certain thoughts, such as thoughts about getting cancer, are dangerous and important, this could lead to you trying to avoid or suppress any thoughts of cancer. Unfortunately, avoiding and suppressing thoughts tends to backfire and lead to the thought becoming more persistent.

This persistence could be interpreted as a sign that the thought is indeed important, and must mean something. Maybe you're having all these thoughts of cancer because you actually have cancer? Now, if you also believe that you need to worry about and monitor your body to stay safe and catch cancer symptoms early, you will be consistently switching between trying not to have these thoughts, while also monitoring your body for signs of cancer.

Together, these beliefs and strategies are likely to lead to prolonged anxiety, and feeling like you don't have control over your mind as you can't stop thinking about cancer, which can activate more coping strategies.

The result is a perpetual state of negative thinking which we call the Cognitive Attentional Syndrome (CAS), an essential concept within Metacognitive Therapy. The CAS is a style of responding to negative thoughts and emotions that consists of (Fisher & Wells, 2009):

- Prolonged/persistent negative thinking, such as worry and rumination,

- Fixating/focusing your attention on threats, such as negative thoughts, feelings or symptoms,

- Coping styles that backfire (such as avoidance and thought control strategies) for a range of reasons, for example by hindering self-regulation or by making negative thoughts and feelings more persistent.

The CAS is found in all types of mental disorders, and is responsible for maintaining and intensifying negative thoughts and feelings.

The negative thoughts and coping styles people experience may vary, but what they all have in common is that the more you engage with your negative thoughts, feelings, and symptoms, the more likely you are to prolong and escalate them. And the worse you feel, the more likely you are to do more to deal with your negative thoughts and symptoms.

But it's the response itself that's fuelling the cycle of mental distress. Not the initial thought, feeling or symptom.

Suddenly, the medicine has become the disease.

This is an important discovery that has revealed a key mechanism in what causes and sustains mental health issues. It led Dr. Adrian Wells to pioneer a highly effective type of psychotherapy that's designed to address the problem at it's core.

Enter: Metacognitive Therapy

MCT helps you understand how current coping strategies could backfire and keep you stuck in cycles of overthinking, worry and rumination. Research shows that challenging your beliefs about thinking helps reduce the CAS, ultimately leading to improved mental health and a healthier relationship with your mind.

Metacognitive Therapy is based on an information processing model of the mind (Wells, 2019). It focuses on changing what we believe about our thoughts and how we respond to them, rather than on the content of the thoughts and feelings themselves.

With the benefits of being transdiagnostic, Metacognitive Therapy is practical, tangible, and effective against a wide range of mental issues. It guides you to interrupt the CAS by becoming more aware of your thinking patterns (known as meta-awareness) and helping you critically examine your current habits of engaging with triggers.

Several clinical studies suggest that Metacognitive Therapy might currently be the most effective therapy in treating common conditions such as anxiety, depression, OCD and PTSD, and it often only requires 8-12 sessions and has a relatively low relapse rate.

What can I expect from MCT treatment?

If you suffer from constant worry and overthinking, try a new approach with Metacognitive Therapy. Unlike other types of therapy, it's a method that doesn't require you to delve into past experiences, as it focuses on your beliefs about your mind, not the content of your thoughts.

MCT helps you rediscover that thoughts and feelings can't harm you, and that you have much more control over your mental processes than you might think. Using simple dialogues, exercises, and strategies to interrupt cycles of overthinking, MCT helps you tackle mental distress in a new and effective way. It offers a structured, manual-based therapy that follows a set sequence of interventions, but an experienced MCT-therapist will tailor treatment to your specific needs and challenges.

It's tough to grasp MCT just by reading about it (after all, these principles challenge our habitual ways of thinking and responding) — so it’s often something that needs to be experienced. These practices might go against your beliefs about the need to solve problems through rumination and worrying. But it's exactly the experiential nature of MCT that makes it so powerful and effective.

Your journey to better mental health starts now, with therapy that works. If you're curious about whether you're a good candidate for MCT, take our quiz to find out more. And if you're ready to overcome overthinking, book a therapy session today.

Selection of consulted references:

Wells, A. (2009). Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. Guilford Press.

Fisher, P., & Wells, A. (2009). Metacognitive Therapy: Distinctive Features (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203881477

Wells, A. (2005). Detached mindfulness in cognitive therapy: A metacognitive analysis and ten techniques. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 23(4), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-005-0018-6

Wells, A. (2019) Breaking the Cybernetic Code: Understanding and Treating the Human Metacognitive Control System to Enhance Mental Health. Front. Psychol. 10:2621. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02621

Wells, A. (2005). Detached mindfulness in cognitive therapy: A metacognitive analysis and ten techniques. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 23(4), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-005-0018-6

Capobianco, L., & Nordahl, H. (2023). A brief history of metacognitive therapy: From cognitive science to clinical practice. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 30(1), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2021.11.002

Nordahl, H., Hjemdal, O., Johnson, S. U., & Nordahl, H. M. (2023). Metakognitiv terapi. Tidsskrift for Norsk psykologforening, 60(12), 781-791. https://doi.org/10.52734/CHIQ3716

Hjemdal, O., Hagen, R., Nordahl, H. M., & Wells, A. (2013). Metacognitive Therapy for Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Nature, Evidence and an Individual Case Illustration. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(3), 301-313. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.01.002